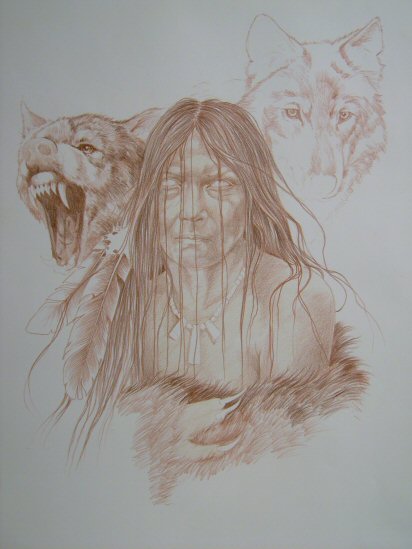

Wolves have held a special place in almost all Native American tribes. They were admired for their

strength and powers of endurance, and taught the tribes many skills.They taught the tribes about sharing, cooperating,

looking after the young and having pride. They showed the native people how to move in the forests -- carefully and

quietly. By living courageously and faithfully, we experience the wonder of being alive, where everything is possible

..."The wolves followed a path of harmony, and they did not like anything to upset their way." "Wolf was chosen by

the Great One to teach the human people how to live in harmony in their families. Wolf was to teach a truth, as each

animal... would do also for the humans to survive.

The Navajo word for wolf, "mai-coh," also means witch, and a person could transform if he or she

donned a wolf skin. So the Europeans were not the only ones with werewolf legends. However, the American tribes have

an overwhelming tendency to look upon the wolf in a much more favorable light. The Navajo themselves have healing

ceremonies which call upon Powers to restore peace and harmony to the ill, and the wolf is one such Power.

"The caribou feeds the wolf, but it is the wolf who keeps the caribou strong."

-Keewatin Eskimo saying

Native American tribes recognized the wolf for its extreme devotion to its family, and many drew

parallels between wolf pack members and the members of the tribe. Also, the wolf's superior and cooperative hunting

skills made it the envy of many tribes. Finally, the wolf was known to defend its home against outsiders, a task with

which each tribe had to contend as well.

Perhaps the tribe with the closest of all associations with the wolf is the Pawnee, in the lands

now known as Nebraska and Kansas. The Pawnee felt such a close kinship that their hand-signal for wolf is the same

as the hand-signal for Pawnee. They were known as the Wolf People even by neighboring tribes. The cyclical appearance

and disappearance of Sirius, the Wolf Star, indicated the wolf coming and going from the spirit world, running down

the trail of the Wolf Road, otherwise known as the Milky Way. The Blackfoot tribe also called our galaxy the Wolf

Trail, or the Route to Heaven. The Pawnee, like the Hidatsa and Oto tribes, used wolf bundles, pouches of skins

from wolves in which to keep and protect treasured implements used for ceremonies and magic.

Wolves figure prominently in the mythology of nearly every Native American tribe. In most Native

cultures, Wolf is considered a medicine being associated with courage, strength, loyalty, and success at hunting.

Like bears, wolves are considered closely related to humans by many North American tribes, and the origin stories

of some Northwest Coast tribes, such as the Quileute and the Kwakiutl, tell of their first ancestors being transformed

from wolves into men. In Shoshone mythology, Wolf plays the role of the noble Creator god, while in Anishinabe mythology

a wolf character is the brother and true best friend of the culture hero. Among the Pueblo tribes, wolves are considered

one of the six directional guardians, associated with the east and the color white. The Zunis carve stone wolf fetishes

for protection, ascribing to them both healing and hunting powers.

Wolves are also one of the most common clan animals in Native American cultures. Tribes with Wolf Clans

include the Creek (whose Wolf Clan is named Yahalgi or Yvhvlke), the Cherokee (whose Wolf Clan name is Aniwahya or Aniwaya,)

the Chippewa (whose Wolf Clan and its totem are called Ma'iingan,) Algonquian tribes like the Lenape, Shawnee and Menominee,

the Huron and Iroquois tribes, Plains tribes like the Caddo and Osage, Southern tribes like the Chickasaw, the Pueblo tribes

of New Mexico, and Northwest Coast tribes like the Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Kwakiutl. Wolf was an important clan crest on the

Northwest Coast and can often be found carved on totem poles. The wolf is also the special tribal symbol of several tribes

and bands, such as the Munsee Delaware, the Mohegans, and the Skidi Pawnee. Some eastern tribes, like the Lenape and Shawnee,

have a Wolf Dance among their tribal dance traditions.

In the Lakota culture were those capable of mediating between the supernatural beings and powers and the common

people called wakan ( wicaša wakan, 'man sacred'; and winyan wakan, 'woman sacred'). Among them are groups comprised of people

who had experienced similar visions. The Wolf Cult (Šung'manitu, or Šunkmahetu, ihanblapi, 'they dream of wolves'). The

members wore wolf skins and were particularly adept at removing arrows from wounded warriors. They also prepared war medicines

(wotawe) for protection against enemies. In Lakota mythology Sung'manitu, the wolf, an animistic night spirit, is regarded as the

source and patron of the hunt and of war

| Lakota Creation Myth

| A woman injured while traveling

| A girl runs away |

| A Woman Who Lived With Wolves

| How Rabbit Fooled Wolf

| Two Wolves |

| The Legend of Wolf Boy

| The Wolf-Man

| Wolf tricks the Trickster |

| The Dog and the Wolf

| Skin-walker |

Lakota Sioux Creation Myth

In the beginning, prior to the creation of the Earth, the gods resided in an undifferentiated celestial domain and humans lived in

an indescribably subterranean world devoid of culture.

Chief among the gods were TakuŠkanŠkan ("something that moves"), the Sun, who is married to the Moon, with whom he has one daughter,

Woĥpe ("falling star").

Old Man and Old Woman, whose daughter Ite ("face") is married to Wind, Tate, with whom she has four sons, the Four Winds.

Among numerous other spirits, the most important is Iktomi ("spider"), the devious trickster. Iktomi conspires with Old Man and Old Woman to increase

their daughter's status by arranging an affair between the Sun and Ite.

The discovery of the affair by the Sun's wife leads to a number of punishments by TakuŠkanŠkan, who gives the Moon her own domain,

and by separating her from the Sun initiates the creation of time.

Old Man, Old Woman, and Ite are sent to Earth, but Ite is separated from the Wind, her husband, who, along with the Four Winds and a fifth wind

presumed to be the child of the adulterous affair, establishes space.

The daughter of the Sun and the Moon, Woĥpe, also falls to earth and later resides with the South Wind, the paragon of Lakota maleness, and the

two adopt the fifth wind, called Wamniomni ("whirlwind").

The Emergence

Alone on the newly formed Earth, some of the gods become bored, and Ite prevails upon Iktomi to find her people, the Buffalo Nation. In the form

of a wolf, Iktomi travels beneath the earth and discovers a village of humans. Iktomi tells them about the wonders of the Earth and convinces one

man, Tokahe ("the first"), to accompany him to the surface.

Tokahe does so and upon reaching the surface through a cave (Wind Cave in the Black Hills), marvels at the green grass and blue sky. Iktomi and Ite

introduces Tokahe to buffalo meat and soup and shows him tipis, clothing, and hunting utensils.

Tokahe returns to the subterranean village and appeals to six other men and their families to travel with him to the Earth's surface.

When they arrive, they discover that Iktomi has deceived them: buffalo are scarce, the weather has turned bad, and they find themselves starving.

Unable to return to their home, but armed with a new knowledge about the world, they survive to become the founders of the Seven Fireplaces.

Lakota tale about a woman who was injured while traveling.

She was found by a wolf pack that took her in and nurtured her. During her time with them, she learned the ways of the wolves, and when she returned

to her tribe, she used her newfound knowledge to help her people. In particular, she knew far before anyone else when a predator or enemy was approaching.

A Sioux Legend

A Lakota girl married a man who promised to treat her kindly, but he did not keep his word. He was unreasonable, fault-finding, and often beat

her. Frantic with his cruelty, she ran away. The whole village turned out to search for her, but no trace of the missing wife was to be found.

Meanwhile, the fleeing woman had wandered about all that day and the next night. The next day she met a man, who asked her who she was. She did not

know it, but he was not really a man, but the chief of the wolves.

"Come with me," he said, and he led her to a large village.

She was amazed to see here many wolves--gray and black, timber wolves and coyotes. It seemed as if all the wolves in the world were there.

The wolf chief led the young woman to a great tipi and invited her in. He asked her what she ate for food.

"Buffalo meat," she answered.

He called two coyotes and bade them bring what the young woman wanted. They bounded away and soon returned with the shoulder of a fresh-killed buffalo calf.

"How do you prepare it for eating?" asked the wolf chief.

"By boiling," answered the young woman.

Again he called the two coyotes. Away they bounded and soon brought into the tipi a small bundle. In it were punk, flint and steel--stolen, it may

be, from some camp of men.

"How do you make the meat ready?" asked the wolf chief.

"I cut it into slices," answered the young woman.

The coyotes were called and in a short time fetched in a knife in its sheath. The young woman cut up the calf's shoulder into slices and ate it.

Thus she lived for a year, all the wolves being very kind to her.

At the end of that time the wolf chief said to her, "Your people are going off on a buffalo hunt. Tomorrow at noon they will be here. You must then

go out and meet them or they will fall on us and kill us."

The next day at about noon the young woman went to the top of a neighboring knoll. Coming toward her were some young men riding on their ponies. She

stood up and held her hands so that they could see her.

They wondered who she was, and when they were close by gazed at her closely.

"A year ago we lost a young woman; if you are she, where have you been," they asked.

"I have been in the wolves' village. Do not harm them," she answered.

"We will ride back and tell the people," they said. "Tomorrow at noon, we shall meet you.

The young woman went back to the wolf village, and the next day went again to a neighboring knoll, though to a different one. Soon she saw the camp

coming in a long line over the prairie. First were the warriors, then the women and tipis.

The young woman's father and mother were overjoyed to see her. But when they came near her the young woman fainted, for she could not now bear the

smell of human kind. When she came to herself she said, "You must go on a buffalo hunt, my father and all the hunters. Tomorrow you must come again,

bringing with you the tongues and choice pieces of the kill."

This he promised to do; and all the men of the camp mounted their ponies and they had a great hunt. The next day they returned with their ponies

laden with the buffalo meat.

The young woman bade them pile the meat in a great heap between two hills which she pointed out to them. There was so much meat that the tops of the

two hills were bridged level between by the meat pile.

In the center of the pile the young woman planted a pole with a red flag. She then began to howl like a wolf, loudly.

In a moment the Earth seemed covered with wolves. They fell greedily on the meat pile and in a short time had eaten the last scrap.

The young woman then joined her own people.

Her husband wanted her to come and live with him again. For a long time she refused. However, at last they became reconciled.

A Lakota Story

told by "Oliver Brown Wolf"

The Woman Who Lived With The Wolves...

Winyan Wan Sungmanitu Tanka Ob Ti...

A Minnekoju camp which had settled down for the winter was raided by Crow Indians. The Crow stole many horses and took a Lakota woman back to their camp.

The Lakota woman was unhappy staying in the Crow camp. She missed her people. Some of the Crow women saw this and took pity on her. They gave her food

and a blanket and told her to hide by a creek near the camp.

Hohwoju oyate eya wani ti pi icuhan kangi wicasa kin sung manu ahi na ota mawicanu pi na nakun Lakota winyan ko akiyagla pi.

Kangi wicasa ti pi heciya winyan ki le aki pi ca titakuye wica kiksuye na lila cante sice na ceya ke, winyan ki ableza pi na heya pi ske, "Sina ki le

ena, woyute ki lena icu, na wakpala ta inahma ye."

She hid herself in the bushes along the banks of the creek. A short time later some of the Crow men came looking for her. While the Lakota woman was

hiding, two wolves came upon her. The wolves growled at her and circled around her. The woman thought the wolves were going to kill her.

But the wolves treated her kindly and guided her along a path to the east. The wolves and the woman traveled together while the Crow were chasing them.

Hoca mni aglala inahma ke, na oiyokpaza ca gla cu ke, icuhan sung'manitu tanka nump el hipi na oksan hlo omanipi ke, takinnas ena kte pi kta kecin ke.

Sung'manitu tanka ki waste ca pi ke ca ob wancok wi yohinyanpata kiya si glu hapi ke.

A raging blizzard caught the woman and her wolf friends in the open prairie. Two more wolves joined them as they walked through the blowing snow. The

small wolf pack and the woman struggled through the snowdrifts and the cold winds.

There is power in this story. The woman was able to get safely away from the Crow because of the blizzard. If one is travelling in a blizzard and

remembers this story- one need not be afraid.

Blaye cokan gla pi ehanl osiceca tanka wan hihunni na icuhan sungmanitu tanka a ke numb hel opa pi ke. Hetan tehiya mani pi eyas hecena gla pi, kangi

wicasa kanyela u pi k'on hetan kawinga pi.

Wooyake ki le wowas'ake yuha. Lakota winyan ki le osiceca ahi ca heon kpapte. Tuwa osiceca icuhan omani ki le wooyake ki kiksuye ehantans takuni toka.

After many days of traveling, the small band reached Squaw Buttes near present day Opal, South Dakota. They came to a cave in the rocks and the wolves

forced her inside. The cave had an awful smell. As her eyes adjusted to the darkness, she saw many wolves in the large den. She thought that the wolves

would tear her apart. Instead the wolves dragged in a deer- tore it apart- and shared it with the woman.

Anpetu ota mani pi ehanl "Winuhcala Paha" eya pica hel ihunni pi, iguga ohan ohloka wan ca sungmanitu tanka ki winyan ki etkita agla pi. Ohloka ki tima

iyaia yukan lila sicamna ke, ista ki ecel itaya ca oksanksan etunwan sung'manitu tanka ki ataya tima hpaya pi ke. Tokinnas ahiyu pi na kiza pi kta kecin

eyas etan tahca wan yaslohan yutimahel icupi ca ob wota.

The wolves were one big family. Many generations of wolves lived together in the cave. Each wolf had its own place in the family. The hunter wolves

brought in the meat. The mother wolf nursed their young. The elder wolves taught the younger wolves the skills of hunting. The other wolves kept watch

over the den. In this way, they all looked after each other.

Sung'manitu tanka ki lena ataya ti ospaye hecapi. Wicooncage tona ataya hel on pi. Hunh hoksi azin kiya hpaya pi. Hunh tanktankpi ca hena wakuwa heca pi.

Hunh ocinsice k'on hena ti awanyanka pi. Sung'manitu tanka wicahcala ki ins cikcikala ki lena tokel wakuwa pi hecel onspe wica kiya pi. Ataya a'wan kica

yanka pi.

The woman made herself a home in the den. She learned to speak and understand the wolves' language. The woman would dry and store the meat for the winter.

She got along well with the wolves, and they got along well with her. Soon she smelled just like the other wolves.

The wolves knew their country well. They always knew whenever the two-legged ones passed through. The wolves usually stayed away from the two-leggeds.

The wolves did not like the way they smelled.

Waniyetu ata hel ob wogla ke na iye nawicahun. Winyan ki lila wakabla na pusye. Sung'manitu tanka ki waste wicalake na insiya wastelaka pi. Winyan ki

insiya sungmanitu tanka mna aya ke.

Sung'manitu tanka ki makoce ki le slolya pi. Tohanl hu numpa ki opta hiyaya pi can slolya pi, sung'manitu tanka ki lena hu numpa ki iheyab sna ecun pi.

Lakota ki tonka mna pi ca he wahtela pi sni.

At turnip digging time of the year- the woman's mother was still mourning. She thought that her daughter had been killed. One day the hunter wolves saw

the mother near the den. The wolves went back and told the woman.

The woman wanted to go back to her people. She was worried that they would not accept her back. The wolves told her to wave her blanket two times if she

wanted to stay with her mother. If she waved once, the wolves would come and take her back to the den.

Wana tinpsinla wasteste ki walehanl winyan ki le hunku ki hehantan wasigla, cuwintku ki t'a kecin. Sung'manitu tanka ki ehake tunweya i pi ca hehan winyan

ki le hunku ki wanyanka pi ca okiyaka pi. Winyan ki wancok taoyate ki ekta gla cin, eyas hekta kiya ikikcu pi ki he slolye sni.

Sung'manitu tanka ki heya pi, tohanl taoyate el ki na, ob on kta ehantans sina ki numpa koz si pi na e e ku cin, ehantans wanjala kos si pi.

When the mother saw her daughter coming, she was so happy to see her that she cried. The woman waved her blanket twice to the wolves who were watching

her from the hills. The wolves saw this and went back to their cave.

The woman's name became Inyan Oti Win - "Woman who lived in the rock". The rock is now considered a sacred area to the Lakota.

Be careful of this tale, because if it is told on a winter night, it might cause a blizzard!

Wana, sung'manitu tanka ki kanyela hunku ki wawopta keya pi ca winyan ki etkiya iyaya. Ata kici yapi na ceya pi. Sina ki numpa koza ca sung'manitu tanka

ki hektakiya kigla pi.

Ho, le winyan ki "Inyan Oti Win" eciya pi ca ohloka ki he Lakota ki wakan glawa pi. Wico'oyake ki le wowos'ake ikoya ke ca waneyetu ehanl Olake ki ungna

osiceca wanji hihunni kte.

How Rabbit Fooled Wolf

Two pretty girls lived not far from Rabbit and Wolf. One day Rabbit called upon Wolf and said "Let's

go and visit those pretty girls up the road." "All right," Wolf said, and they started off. When they

got to the girls' house, they were invited in, but both girls took a great liking to Wolf and paid all

their attention to him while Rabbit had to sit by and look on. Rabbit of course was not pleased by

this and he soon said, "We had better be going back." "Let's wait a while longer," Wolf replied and

they remained until late in the day. Before they left, Rabbit found a chance to speak to one of the

girls so that Wolf could not overhear and he said, "The one you've been having so much fun with is

my old horse." "I think you are lying," the girl replied. "No, I am not. You shall see me ride him

up here tomorrow." "If we see you ride him up here," the girl said with a laugh, "we'll believe he's

only your old horse." When the two left the house, the girls said, "Well, call again."

Next morning

Wolf was up early, knocking on Rabbit's door. "It's time to visit those girls again," he announced.

Rabbit groaned. "Oh, I was sick all night," he answered "and I hardly feel able to go." Wolf kept

urging him, and finally Rabbit said: "If you will let me ride you, I might go along to keep you

company." Wolf agreed to carry him astride of his back. But then Rabbit said, "I would like to put

a saddle on you so as to brace myself." When Wolf agreed to this, Rabbit added: "I believe it would

be better if I should also bridle you." Although Wolf objected at first to being bridled, he gave in

when Rabbit said he did not think he could hold on and manage to get as far as the girls' house

without a bridle. Finally Rabbit wanted to put on spurs. "I am too ticklish," Wolf protested. "I

will not spur you with them," Rabbit promised. "I will hold them away from you, but it would be

nicer to have them on." At last Wolf agreed to this, but he repeated: "I am very ticklish. You must

not spur me." "When we get near the girls' house," Rabbit said "we will take everything off you and

walk the rest of the way."

And so they started up the road, Rabbit proudly riding upon Wolf's back.

When they were nearly in sight of the house Rabbit raked his spurs into Wolf's sides, and Wolf

galloped full speed right by the house. "Those girls have seen you now," Rabbit said. "I will tie

you here and go up to see them and try to explain everything. I'll come back after a while and get

you." And so Rabbit went back to the house and said to the girls: "You both saw me riding my old

horse, did you not?" "Yes," they answered, and he sat down and had a good time with them. After a

while Rabbit thought he ought to untie Wolf and he started back to the place where he was fastened.

He knew that Wolf must be very angry with him by this time, and he thought up a way to untie him and

get rid of him without any danger to himself. He moved around a thin hollow log and began beating upon it

as if it were a drum. Then he ran up to Wolf as fast as he could go, crying out: "The soldiers are

hunting for you! You heard their drum. The soldiers are after you." The Wolf was very much frightened

of soldiers. "Let me go, let me go!" he shouted. Rabbit was purposely slow in untying him and had

barely freed him when Wolf broke away and ran as fast as he could into the woods. Then Rabbit returned

home, laughing to himself over how he had fooled Wolf and feeling satisfied that he could have the

girls to himself for a while.

Near the girls' house was a large peach orchard and one day they asked

Rabbit to shake the peaches off the tree for them. They went to the orchard together and he climbed

up into a tree to shake the peaches off. While he was there, Wolf suddenly appeared and called out:

"Rabbit, old fellow, I'm going to even the score with you. I'm not going to leave you alone until I

do." Rabbit raised his head and pretended to be looking at some people off in the distance. Then he

shouted from the treetop: "Here is that fellow, Wolf, you've been hunting for!" At this, Wolf took

fright and ran away again. Some time after this, Rabbit was resting against a tree trunk that leaned

toward the ground. When he saw Wolf coming along toward him, he stood up so that the bent tree trunk

pressed against his shoulder. "I have you now," said Wolf, but Rabbit quickly replied: "Some people

told me that if I would hold this tree up with the great power I have they would bring me four hogs

in payment. Now, I don't like hog meat as well as you do, so, if you take my place, they'll give the hogs

to you." Wolf's greed was excited by this, and he said he was willing to hold up the tree. He squeezed

in beside Rabbit, who said, "You must hold it tight, or it will fall down." Rabbit then ran off, and

Wolf stood with his back pressed hard against the bent tree trunk until he finally decided he could

stand it no longer. He jumped away quickly, so that the tree would not fall upon him. Then he saw that it

was only a leaning tree rooted in the earth. "That Rabbit is the biggest liar," he cried. "If I can

catch him I'll certainly fix him."

After that, Wolf hunted for Rabbit every day until he found him

lying in a nice grassy place. He was about to spring upon him when Rabbit said "My friend, I've been

waiting to see you again. I have something good for you to eat. Somebody killed a pony out there in

the road. If you wish I'll help you drag it out of the road to a place where you can make a feast of

it." "All right," Wolf said, and he followed Rabbit out to the road where a pony was lying asleep.

"I'm not strong enough to move the pony by myself," said Rabbit "so I'll tie its tail to yours and

help you by pushing." Rabbit tied their tails together carefully so as not to awaken the pony. Then

he grabbed the pony by the ears as if he were going to lift it up. The pony woke up, jumped to its

feet, and ran away, dragging Wolf behind. Wolf struggled frantically to free his tail but all he could

do was scratch on the ground with his claws. "Pull with all your might," Rabbit shouted after him.

"How can I pull with all my might," Wolf cried, "when I'm not standing on the ground?" By and by,

however, Wolf got loose and then Rabbit had to go into hiding for a very long, long time.

Two Wolves

A Cherokee Legend

An old Indian Grandfather said to his grandson who came to him with anger at a friend who had done

him an injustice.

"Let me tell you a story. I too, at times, have felt a great hate for those that have taken so

much, with no sorrow for what they do. But hate wears you down, and does not hurt your enemy. It

is like taking poison and wishing your enemy would die. I have struggled with these feelings many

times."

He continued...

"It is as if there are two wolves inside me; One is good and does no harm. He lives in harmony with

all around him and does not take offense when no offense was intended. He will only fight when it is

right to do so, and in the right way. He saves all his energy for the right fight.

But the other wolf, ahhh!

He is full of anger. The littlest thing will set him into a fit of temper. He fights everyone, all

the time, for no reason. He cannot think because his anger and hate are so great. It is helpless

anger, for his anger will change nothing. Sometimes it is hard to live with these two wolves inside

me, for both of them try to dominate my spirit."

The boy looked intently into his Grandfather's eyes and asked...

"Which one wins, Grandfather?"

The Grandfather smiled and quietly said...

"The one I feed."

Legend of Wolf Boy

A Kiowa Legend

There was a camp of Kiowa. There were a young man, his wife, and his brother. They set out by

themselves to look for game. This young man would leave his younger brother and his wife in camp and go out to

look for game. Every time his brother would leave, the boy would go to a high hill nearby and sit there all day

until his brother returned. One time before the boy went as usual to the hill, his sister-in-law said, "Why are

you so lonesome?" Let us be sweethearts. "The boy answered, "No, I love my brother and I would not want to do that."

She said, "Your brother would not know. Only you and I would know. He would not find out." "No, I think a great

deal of my brother. I would not want to do that."

One night as they all went to sleep the young woman went to where the boy used to sit on the hill.

She began to dig. She dug a hole deep enough so that no one would ever hear him. She covered it by placing a hide

over the hole, and she made it look so natural so nobody would notice it. She went back to the camp and laid down.

Next day the older brother went hunting and the younger brother went to where he used to sit. The young woman

watched him and saw him drop out of sight. She went up the hill and looked into the pit and said, "I guess you want

to make love now. If you are willing to be my sweetheart I will let you out. If not, you will have to stay in there

until you die." The boy said, "I will not." After the young man returned home, he asked his wife where his little

brother was. She said, "I have not seen him since you left, but he went up on the hill."

That night as they went to bed the young man said to his wife that he thought he heard a voice

somewhere. She said, " It is only the Wolves that you hear." The young man did not sleep all night. He said to his

wife, "You must have scolded him to make him go; he may have gone back home." I did not say anything to him. Every

day when you go hunting he goes to that hill." Next day they broke camp and went back to the main camp to see if

he was there. He was not there. They concluded that he had died. His father and mother cried over him.

The boy staying in the pit was crying; he was starving. He looked up and saw something. A Wolf

was pulling off the old hide. The Wolf said, "Why are you down there?" The boy told him what happened, that the

woman caused him to be in there. The Wolf said, "I will get you out. If I get you out, you will be my son." He

heard the Wolf howling. When he looked up again, there was a pack of Wolves. They started to dig in the side of

the pit until they reached him and he could crawl out. It was very cold. As night came on, the Wolves lay all

around him and on top of him to keep him warm.

Next morning the Wolves asked what he ate. He said that he ate meat. So the Wolves went out and

found Buffalo and killed a calf and brought it to him. The boy had nothing to butcher it with, so the Wolf tore

the calf to pieces for the boy to get out what he wanted. The boy ate till he was full. The Wolf who got him out

asked the others if they knew where there was a flint knife. One said that he had seen one somewhere. He told him

to get it. After that, when the Wolves killed for him he would butcher it himself.

Some time after that, a man from the camp was out hunting, and he observed a pack of Wolves and

among them a man. He rode up to see if he could recognize this man. He got near enough only to see that it was a

man. He returned to camp and told the people ne had seen a man with some Wolves. They considered that it might be

the young man who had been lost some time before. The camp had killed off all the Buffalo. Some young men after

butchering had left to kill Wolves (as they did after killing Buffalo). They noticed a young man with a pack of

Wolves. The Wolves saw the men, and they ran off. The young man ran off with them.

Next day the whole camp went out to see who the young man was. The saw the Wolves and the young

man with them. They pursued the young man. They overtook him and caught him. He bit them like a Wolf. After they

caught him, they heard the Wolves howling in the distance. The young man told his father and brother to free him

so he could hear what the Wolves were saying. They said if they loosened him, he would not come back. However they

loosened him and he went out and met the Wolves. Then he returned to camp.

"How did you come to be among them?" asked the father and brother. He told how his sister-in-law

had dug the hole, and he fell in, and the Wolves had gotten him out, and he had lived with them ever since.

The Wolf had said to him that someone must come in his place, that they were to wind Buffalo gut

around the young woman and send her. The young woman's father and mother found out what she had done to the boy.

They said to her husband that she had done wrong and for him to do as the Wolf had directed and take her to him

and let him eat her up. So the husband of the young woman took her and wound the guts around her and led her to

where the Wolf had directed. The whole camp went to see, and the Wolf Boy said, "Let me take her to my father

Wolf." Then he took her and stopped at a distance and howled like a Wolf, and they saw the Wolves coming from

everywhere. He said to his Wolf father, "Here is the one you were to have in my place." The Wolves came and tore her up.

The Wolf-Man

A Blackfoot Legend

There was once a man who had two bad wives. They had no shame. The man thought if he moved

away where there were no other people, he might teach these women to become good, so he moved his lodge away

off on the prairie. Near where they camped was a high butte, and every evening about sundown, the man would

go up on top of it, and look all over the country to see where the buffalo were feeding, and if any enemies

were approaching. There was a buffalo skull on the hill, which he used to sit on.

"This is very lonesome," said one woman to the other, one day. "We have no one to talk with

nor to visit."

"Let us kill our husband," said the other. "Then we will go back to our relations and have

a good time."

Early in the morning, the man went out to hunt, and as soon as he was out of sight, his wives

went up on top of the butte. There they dug a deep pit, and covered it over with light sticks, grass, and dirt,

and placed the buffalo skull on top.

In the afternoon they saw their husband coming home, loaded down with meat he had killed. So

they hurried to cook for him. After eating, he went up on the butte and sat down on the skull. The slender sticks

gave way, and he fell into the pit. His wives were watching him, and when they saw him disappear, they took down

the lodge, packed everything on the dog travois, and moved off, going toward the main camp. When they got near

it, so that the people could hear them, they began to cry and mourn.

"Why is this?" they were asked. "Why are you mourning? Where is your husband?"

"He is dead," they replied. "Five days ago he went out to hunt, and he never came back." And

they cried and mourned again.

When the man fell into the pit, he was hurt. After a while he tried to get out, but he was so

badly bruised he could not climb up. A wolf, travelling along, came to the pit and saw him, and pitied him.

Ah-h-w-o-o-o-o! Ah-h-w-o-o-o-o! he howled, and when the other wolves heard him they all came running to see what

was the matter. There came also many coyotes, badgers, and kit-foxes.

"In this hole," said the wolf, "is my find. Here is a fallen-in man. Let us dig him out, and we

will have him for our brother."

They all thought the wolf spoke well, and began to dig. In a little while they had a hole close

to the man. Then the wolf who found him said, "Hold on; I want to speak a few words to you." All the animals

listening, he continued, "We will all have this man for our brother, but I found him, so I think he ought to live

with us big wolves." All the others said that this was well; so the wolf went into the hole, and tearing down the

rest of the dirt, dragged the almost dead man out. They gave him a kidney to eat, and when he was able to walk a

little, the big wolves took him to their home. Here there was a very old blind wolf, who had powerful medicine. He

cured the man, and made his head and hands look like those of a wolf. The rest of his body was not changed.

In those days the people used to make holes in the pis'kun walls and set snares, and when wolves

and other animals came to steal meat, they were caught by the neck. One night the wolves all went down to the pis'kun

to steal meat, and when they got close to it, the man-wolf said: "Stand here a little while. I will go down and fix

the places, so you will not be caught." He went on and sprung all the snares; then he went back and called the wolves

and others, the coyotes, badgers, and foxes, and they all went in the pis'kun and feasted, and took meat to carry home.

In the morning the people were surprised to find the meat gone, and their nooses all drawn out.

They wondered how it could have been done. For many nights the nooses were drawn and the meat stolen; but once,

when the wolves went there to steal, they found only the meat of a scabby bull, and the man-wolf was angry, and

cried out: "Bad-you-give-us-o-o-o! Bad-you-give-us-o-o-o-o!"

The people heard him, and said: "It is a man-wolf who has done all this. We will catch him." So

they put pemmican and nice back fat in the pis'kun, and many hid close by. After dark the wolves came again, and

when the man-wolf saw the good food, he ran to it and began eating. Then the people all rushed in and caught him

with ropes and took him to a lodge. When they got inside to the light of the fire, they knew at once who it was.

They said, "This is the man who was lost."

"No," said the man, "I was not lost. My wives tried to kill me. They dug a deep hole, and I fell

into it, and I was hurt so badly that I could not get out; but the wolves took pity on me and helped me, or I

would have died there."

When the people heard this, they were angry, and they told the man to do something.

"You say well," he replied. "I give those women to the I-kun-uh'-kah-tsi; they know what to do."

After that night the two women were never seen again.

Wolf tricks the Trickster

A Shoshone Legend

The Shoshoni people saw the Wolf as a creator God and they respected him greatly.

Long ago, Wolf, and many other animals, walked and talked like man.

Coyote could talk, too, but the Shoshoni people kept far away from him because he

was a Trickster, somebody who is always up to no good and out to double-cross you.

Coyote resented Wolf because he was respected by the Shoshoni. Being a devious

Trickster, Coyote decided it was time to teach Wolf a lesson. He would make the Shoshoni people

dislike Wolf, and he had the perfect plan. Or so he thought.

One day, Wolf and Coyote were discussing the people of the land. Wolf claimed

that if somebody were to die, he could bring them back to life by shooting an arrow under them.

Coyote had heard this boast before and decided to put his plan into action.

Wearing his most innocent smile he told Wolf that if he brought everyone back to

life, there would soon be no room left on Earth. Once people die, said Coyote, they should remain dead.

If Wolf takes my advice, thought Coyote, then the Shoshoni people would hate

Wolf, once and for all.

Wolf was getting tired of Coyote constantly questioning his wisdom and knew he was

up to no good, but he didn't say anything. He just nodded wisely and decided it was time to teach

Coyote a lesson.

A few days after their conversation, Coyote came running to Wolf. Coyote's fur was

ruffled and his eyes were wide with panic.

Wolf already knew what was wrong: Coyote's son had been bitten by Rattlesnake and

no animal can survive the snake's powerful venom.

Coyote pleaded with Wolf to bring his son back to life by shooting an arrow under

him, as he claimed he could do.

Wolf reminded Coyote of his own remark that people should remain dead. He was no

longer going to bring people back to life, as Coyote had suggested.

The Shoshoni people say that was the day Death came to the land and that, as a

punishment for his mischievous ways, Coyote's son was the first to die.

No one else was ever raised from the dead by Wolf again, and the people came to

know sadness when someone dies. Despite Coyote's efforts, however, the Shoshoni didn't hate Wolf.

Instead, they admired his strength, wisdom and power, and they still do today.

The Dog and the Wolf

Discouraged after an unsuccessful day of hunting, a hungry Wolf came on a well-fed Mastiff. He could

see the Dog was having a better time of it than he was, and he inquired what the Dog had to do to

stay so well-fed. "Very little, guard the house, show fondness to the master, be submissive to the

rest of the family and you are well fed and warmly lodged.

The Wolf thought this over carefully. He risked his own life almost daily, had to stay out in the

worst of weather, and was never assured of his meals. He thought he would try another way of living.

As they were going along together the Wolf saw a place around the neck of Dog where the hair had been worn

thin. He asked what this was, and the Dog said it was nothing, "just the place where my collar and

chain rub." The Wolf stopped short. "Chain?" he asked. "You mean you are not free to go where you

choose?" "No," said the Dog, "but what does that mean?" "Much," answered the Wolf as he trotted

off. "Much"

Skin-walker

In some Native American legends, a skin-walker is a person with the supernatural ability to

turn into any animal he or she desires. To be able to transform, legend sometimes requires that the skinwalker

does wear a pelt of the animal, though this is not always considered necessary.

Similar lore can be found in cultures throughout the world and is often referred to as

shapeshifting by anthropologists.

Navajo skinwalker: the yee naaldlooshii

Possibly the best documented skinwalker beliefs are those relating to the Navajo yee

naaldlooshii (literally "with it, he goes on all fours" in the Navajo language). A yee naaldlooshii is

one of several varieties of Navajo witch (specifically an ’ánt’iihnii or practitioner of the Witchery

Way, as opposed to a user of curse-objects (’adagash) or a practitioner of Frenzy Way (’azhitee)).

Technically, the term refers to an ’ánt’iihnii who is using his (rarely her) powers to travel in animal

form. In some versions, men or women who have attained the highest level of priesthood are called

"clizyati", "pure evil", then they commit the act of killing a member of their family, and then have

thus gained the evil powers that are associated with skinwalkers.

The ’ánt’iihnii are human beings who have gained supernatural power by breaking a

cultural taboo. Specifically, a person is said to gain the power to become a yee naaldlooshii upon

initiation into the Witchery Way. Both men and women can become ’ánt’iihnii and therefore possibly

skinwalkers, but men are far more numerous. It is generally thought that only childless women can

become witches.

Although it is most frequently seen as a coyote, wolf, owl, fox, or crow, the yee

naaldlooshii is said to have the power to assume the form of any animal they choose, depending on what

kind of abilities they need. Witches use the form for expedient travel, especially to the Navajo equivalent

of the 'Black Mass', a perverted song (and the central rite of the Witchery Way) used to curse instead

of to heal. They also may transform to escape from pursuers.

Some Navajo also believe that skinwalkers have the ability to steal the "skin" or body

of a person. The Navajo believe that if you lock eyes with a skinwalker, they can absorb themselves into

your body. It is also said that skinwalkers avoid the light and that their eyes glow like an animal's

when in human form, and when in animal form their eyes do not glow as an animal's would.

A skinwalker is usually described as naked, except for an animal skin. Some Navajos

describe them as a mutated version of the animal in question. The skin may just be a mask, like those

which are the only garment worn in the witches' song.

Because animal skins are used primarily by skinwalkers, the pelt of animals such as

bears, coyotes, wolves, and cougars are strictly tabooed. Sheepskin and buckskin are probably two of

the few hides used by Navajos; the latter is used only for ceremonial purposes.

Often, Navajos will tell of their encounter with a skinwalker, though there is a lot

of hesitancy to reveal the story to non-Navajos, or to talk of such frightening things at night. Sometimes

the skinwalker will try to break into the house and attack the people inside, and will often bang on the

walls of the house, knock on the windows, and climb onto the roofs. Sometimes, a strange, animal-like

figure is seen standing outside the window, peering in. Other times, a skinwalker may attack a vehicle

and cause a car accident. The skinwalkers are described as being fast, agile, and impossible to catch.

Though some attempts have been made to shoot or kill one, they are not usually successful. Sometimes a

skinwalker will be tracked down, only to lead to the house of someone known to the tracker. As in

European werewolf lore, sometimes a wounded skinwalker will escape, only to have someone turn up later

with a similar wound which reveals them to be the witch. It is said that if a Navajo was to know the

person behind the skinwalker they had to pronounce the full name, and about three days later that person

would either get sick or die for the wrong that they have committed.

Legend has it skinwalkers can have the power to read human thoughts. They also possess

the ability to make any human or animal noise they choose. A skinwalker may use the voice of a relative

or the cry of an infant to lure victims out of the safety of their homes.

Skinwalkers use charms to instill fear and control in their victims. Such charms include

human bone beads launched by blowguns, which embed themselves beneath the surface of the skin without

leaving a mark, and human bone dust which can cause paralysis and heart failure. Skinwalkers have been

known to find traces of their victim's hair, wrap it around a pot shard, and place it into a tarantula

hole. Even live rattlesnakes are known to be used as charms by the skinwalker.

According to Navajo myth, the only way to successfully shoot a skinwalker is to dip

bullets into white ash. Often people attempting to shoot a skinwalker find their weapon jamming or

frozen. Other times the rounds fire but have no effect.

If spotted, the skinwalker will run away, and, if chased, his foot print will not be

present even if only a few feet away. Also, if it is fired at even at point blank range, it will have

no effect, and it may attack, or run off. The only way to kill a skinwalker if no white ash is present

is to shoot the skinwalker in human form.

History of the skinwalker

There are a few legends to the roots of the skinwalker. One such comes from the long

walk. During this time, Skinwalkers would shapeshift to flee the horrors of living under the torture

of the white man. It made them faster and the soldiers were unable to detect them running.

Another was that the skinwalker was started by the poor community in the old days. At

night a skinwalker would dress up in ceremonial dress and go from door to door. The more well-off people

would leave something outside their hogan for the skinwalker. Eventually with times changing people forgot

about the skinwalker and stopped leaving things for them. This led to resentment among the poor and they

turned on those who forgot them. And now they exist as a hateful people out for revenge.

Finally there are those who tell of the skinwalker as a medicine man. It was started

by the Lakota, when they would dress up like wolves to hunt the bison. The tradition made its way to

the Navajo people and it was adopted by the medicine men. However, in this legend it does not explain

how the Skinwalker became full of hate for his fellow tribe.

Many Navajos believe the Anasazi had a lot to do with the witchcraft that runs in their

community. Thus, Anasazi ruins and graves are strictly taboo. It's said that a skinwalker will use the

bones of the Anasazi for their charms.

According to Raymond Friday Locke in the Book of the Navajo, the practice of animal

emulation began with a hunter who thought of using the head of a deer so that he could approach them

more closely to kill them. He was unsuccessful until the Gods came and showed him not only how to make

the mask but how to emulate the animal. The practice of wearing the skins of the deer and emulating

them began for the purpose of hunting. Locke also links the practice of witchcraft involving animal

emulation and shape shifting to the Navajo folk tale of Coyote's wife. Believing that Coyote had been

murdered, his wife takes the form of a bear and begins to curse and slay her husband's killers with

witchcraft. The association of skin-walkers with Coyote is a prevalent belief in both their common

usage of coyote skins and reputations of being tricksters. Skinwalkers are known as a Native American

version of a Loup-garou. Even children have been known to become a skinwalker.

Totem animals and the art of the Medicine Man

The Navaho people have a very strong relationship bond with Mother Earth and the plant

and animal kingdoms that were so much a part of their everyday lives. Certain animals were more sacred

to some individuals, families and tribes. These animals could be said to bless, heal or guide the people

and become totem animals.

Totem animals are honored with their likeness in the dress, dance, music and artwork

of the people. The traits and characteristics of the totem animals could be gifted to the people who

developed a deep friendship with the spirits of these helpful creatures. Some individuals developed

such a deep connection with nature and her magic that they could talk with the plants and animals and

bring knowledge of medicine and other healing arts to their tribes. These few adepts became medicine

men, healers, or wise ones.

Medicine men were known to be able to travel to other states of being. It was through

the gifts of their totem animals that this travel was made. They were often seen wearing the skin of

the animal that granted them this power and would sometimes be seen in animal form.

Often ancestors and heroes would appear as animals important or sacred to the family

or tribe, or as an animal the individual was known for. People especially reported seeing these strangely

human animals when receiving good fortune or divine messages. Some would hear the animals speak to them,

act as a human would or witness impossible colors or breeds that do not exist.

Like the folk and nature religions in other parts of the world are called witches, these

sacred beliefs are greatly misunderstood and demonized by a fearful society. To use the term skin-walker

to speak of violence, hatred, witchcraft and demons is more provocative than to understand the path of a

healer, a wise one or a medicine man.